In the 1950s, the decade when I was a kid, the

popularity of the gangster movie genre was fueled by real-life headlines and

the success of TV’s THE UNTOUCHABLES. In the ‘60s, movie hoods were

briefly overshadowed by the Bond craze: even when emissaries of the American

Mafia appeared in the 007 movie universe in GOLDFINGER, they were simply there

to support the title mastermind’s criminal enterprise. Arguably, the

notoriety of 1967’s POINT BLANK and BONNIE AND CLYDE whetted the public’s

appetite for a modern era of mob films; the epic popularity of THE GODFATHER

followed.

SCARFACE and GOODFELLAS were the hallmark

gangster movies of the ‘80s, followed in the mid-’90s by PULP FICTION and its

imitators. Tarantino’s style continued to influence moviemakers into the

2000s, if Guy Ritchie, SMOKIN’ ACES, LUCKY NUMBER SLEVIN, and BOONDOCK SAINTS

are any indication. Ritchie’s ROCKnROLLA (2008) may have been the last

gasp of the jokey, time-twisting Tarantino approach to mobster narrative,

at least for now. I have a feeling that we’ll experience a wave of new

Tarantino imitations in the next couple of years, in the form of emerging

thirty-five-ish writers and directors who saw PULP FICTION at the

impressionable age of 12 or 13.

I watched a bunch of new -- that is, post-2010

-- gangster films recently. On the whole, they were varied in

setting and approach, but all were comfortably (or uncomfortably, depending on

your fondness for what some would call genre conventions; others, cliches)

rooted in classic traditions.

KILL THE IRISHMAN (2011) and THE ICEMAN (2013)

purport to be based on true stories from the 1970s. The Irishman, Danny

Greene (Ray Stevenson), rises from Cleveland dockworker to money-making Mafia

associate by impressing the local mob, then incurs their wrath when he turns

informant for the FBI. The Iceman, Richard Kuklinski, follows a similar

trajectory: he becomes a hit man for Roy DeMeo’s Brooklyn crew, then becomes

too enterprising for the paranoid DeMeo’s comfort.

THE ICEMAN is the stronger movie, thanks to

Michael Shannon’s performance as Kuklinski and edgy support by an

unrecognizable Chris Evans as fellow killer Robert Pronge. Both movies

tip their hats to their cinematic predecessors by central casting of supporting

roles from mob movies and shows past: Ray Liotta and Robert Davi in THE ICEMAN,

Paul Sorvino, Vinnie Jones, Christopher Walken, Steve Schirripa,and Tony

LoBianco in KILL THE IRISHMAN.

Walken and Al Pacino are aging mobsters in

STAND UP GUYS (2012); maybe more precisely stated, they play Walken and Pacino

playing mobsters. Walken’s boss forces Walken to take a contract on his

old friend Pacino when Pacino is released from prison. The plot is

predictable, but then that’s the point of casting iconic actors by type, isn’t

it?

Walter Hill’s BULLET TO

THE HEAD (2013), based on a graphic novel, teams Sylvester Stallone as a hit

man with a Washington, D.C., Asian-American detective (Taylor Kwon) to bust a

ring of mobsters and power brokers in New Orleans. I’ve never quite

shared many critics’ fondness for Hill. I’m not sure who the real auteur

here is supposed to be, him or Stallone, although the movie repeats motifs from

Hill’s past movies, 48 HRS and RED HEAT. As the evil mob henchman, in a

role that calls for the heft of a modern Jack Palance or Ernest Borgnine, Jason

Mamoa is as empty of charisma as he was in the 2011 remake of CONAN THE

BARBARIAN. Kwon’s cop wins a prize for stupidity as he continues to trust

the New Orleans PD after it becomes painfully clear that they are in the bad

guys’ pockets.

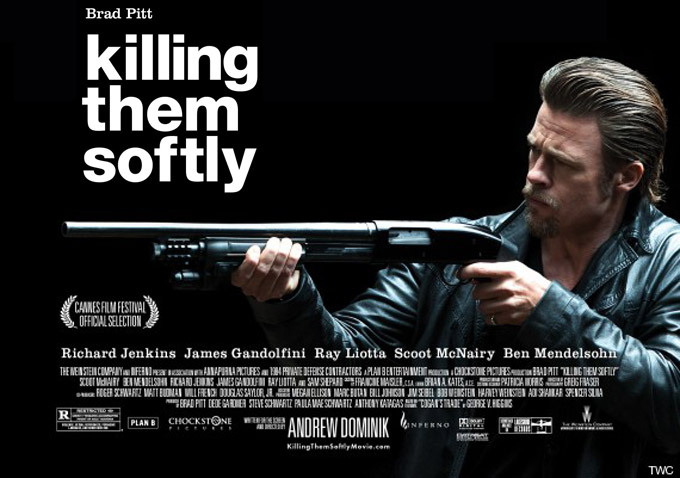

KILLING THEM SOFTLY (2013), based on George V.

Higgins’ COGAN’S TRADE, updates Higgins’ 1974 setting to 2008. As politicians

attempt to stabilize the collapsing American economy in TV clips of Bush and

Obama that play in the background of several scenes, the Boston mob tries to

stabilize their local criminal economy by finding and executing two gunmen who

robbed a mob-protected card game. I rather liked the style of the film,

which punctuates long, conversation-driven scenes with sudden bursts of brutal

violence. The best single visual is a

shot of a shivering little stolen chihuahua on a leash, looking up at the two

gunmen on a bleak street corner as they plan their ill-fated holdup.

I haven’t read the Higgins novel, so I don’t

know how he described his hit man character, Jackie Cogan; Brad Pitt gives it a

heartfelt try, but I kept thinking how much more believable Lee Marvin or Henry

Silva would have been. Ray Liotta is in this one too as a hapless hood,

and the late James Gandolfini as another hit man; come to think of it,

Gandolfini should have played Cogan, and Pitt should have played his

role. I think there is a homage to David Lynch’s BLUE VELVET when “Love

Letters,” the old Ketty Lester ballad, plays in the background of a slow-motion

scene of a rub-out.

Tom Hardy anchors LAWLESS (2012) as a

moonshiner in the Blue Ridge in the 1930s in another “based on a true story’

script. The film starts well, with Guy Pearce suitably nasty as a crooked

Revenue agent in a role that seems to combine Richard Widmark’s and Patrick

McGoohan’s characters from the 1969 movie version of Elmore Leonard’s THE

MOONSHINE WAR. But the ending collapses into a far-fetched, over-the-top

shootout between the bootleggers and the law; less would have been better.

VIVA RIVA! (2010) has the most exotic location

of the recent gang movies: Kinshasa, the capital of the Republic of Congo,

where go-getter Riva hijacks a valuable cargo of gasoline the way the 1930s

gangsters hijacked shipments of booze. This does not sit well with the

local boss, Azor. The setting may be modern urban Africa, but Riva --

like the Irishman and the Iceman -- follows a pattern that goes back at least

to James Cagney’s Tom Powers and Edward G. Robinson’s Rico Bandello, eighty

years ago: “a steady upward progress followed by a very precipitate fall,” in

Robert Warshow’s words. Warshow wrote his essay on the movie gangster in

1948; I don’t know whether he would have been surprised or reassured

that, 65 years later, today’s productions continue to ply the same

formula.

#

# # #

No comments:

Post a Comment