Inside the head of Sam Peckinpah

So the great

director's films are about violence? Not really. Are they about honour? Hardly.

In fact, says Rick Moody, Sam Peckinpah offered us realism - albeit of a very

particular kind

Rick

Moody

The Guardian, Thursday 8

January 2009

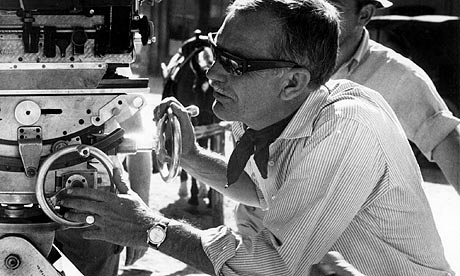

'Undisputed poet of

alcoholic cinema' ... Sam Peckinpah on the set of The Wild Bunch. Photograph:

Ronald Grant Archive

"Now, most funeral orations, Lord, lie about

a man," - so says David Warner, in his memorable turn as Joshua, the

fraudulent preacher in Sam Peckinpah's The Ballad of Cable Hogue, from 1970.

The same can be said of most film criticism - that it dissimulates or

exaggerates about the film, about the director, about the movement, about the

art. So let's aspire in this revisionist essay on Peckinpah to tell the truth.

Although it's worth noting that when you believe what characters say in a

Peckinpah film, you play right into the director's malevolent hands.

.

Nevertheless, the first point that must be made,

here in the 21st century, is that Peckinpah's films are not terribly violent.

That's how he made his reputation: as "Bloody Sam", the man who never

met a bucket of theatrical blood he wasn't willing to splash around, and who

always made certain you knew when the blood was about to flow, by means of slow

motion. Still, by today's standards, the better part of the Peckinpah canon is

not terribly violent - not when judged against today's rivers of gore. There

are, in Peckinpah, no fountaining bodies, no bits of brain tissue splattered

about. Anything released in the last 20 years is quite a bit more repellent.

Seen any of those Saw movies?

Ride the High Country is a good place to start

for the uninitiated. Released in 1962, it scarcely departs from the western as

we understand it. There's the good guy, Steve Judd, and the bad guy, Gil

Westrum, and they behave according to type for the first reel, at least until

they get into the business of saving a young, impetuous romantic (the very

first film role of Mariette Hartley) from her up-country fiance. Then the good

guys and bad guys get curiously admixed, till it is hard to tell which is

which. Indeed, Hartley's impetuous tomboy and Randolph Scott's old cowpoke

have, toward the end, an exchange on the ubiquity of gray areas between right

and wrong.

This exchange could serve as a template for the

morality of the entire Peckinpah oeuvre. Still, the threatened gang rape in

High Country happens mainly by implication, and there is little here of

Peckinpah, master of the high-noon showdown. Even in the midst of the climactic

shootout, the camaraderie between the "bad" Westrum and the "good"

Scott, as they pick off a posse of far worse mountain men, is anything but

removed from the western genre. The shootout involves a lot of grimacing, and

there is ample time, despite perforations, for Scott's last pronouncements.

After which the orchestra swells!

for the rest go here:

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jan/09/sam-peckinpah-retrospective

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jan/09/sam-peckinpah-retrospective

No comments:

Post a Comment