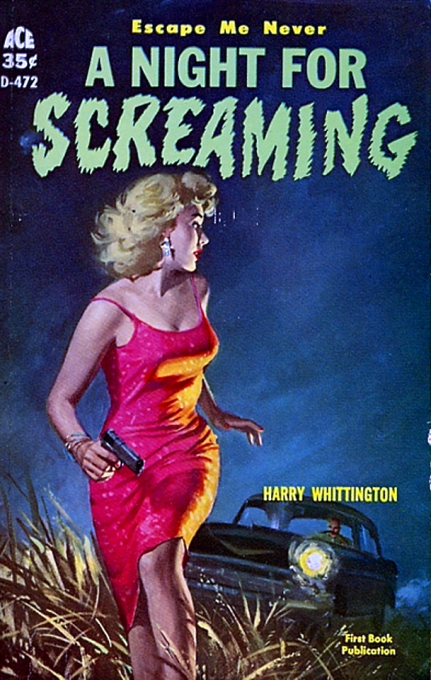

Ed here: This is probably my favorite lurid pb cover. Others might offer more grace and style but this one has it all. Night, a desperate babe, a gun, a swamp, an iconic killer car. Wow.

I really like the following piece. A few weeks ago The New Yorker ran what I thought was a snooty and snotty piece about paperbacks. Though it was packed with information I really enjoyed the tone, when it came to bestselling pbs, was condescending at best. Was Mickey Spillane the source of all social evil in the 1950s? The article did everything except lynch him.

How Pulp Fiction Saved Literature

by Wendy Smith from The Daily Beast

for the entire piece go here:

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/08/how-pulp-fiction-saved-literature.html

The covers were often trashy, the contents were often high art, but the low cost of the ubiquitous paperback created millions of new readers in America.

Paula Rabinowitz’s American Pulp, her analysis of the impact of cheap paperback books on American culture is so enthusiastic and informative that her occasional lapses into impenetrable academese can be forgiven. Readers scratching their heads over such phrases as “this period, modernity, emphatically ushers in privacy itself” are advised to turn immediately for relief to the marvelous color plates of early paperback covers in all their tawdry glory.

One of the many pleasures in American Pulp (subtitled How Paperbacks Brought Modernism to Main Street) is Rabinowitz’s knowledgeable survey of how those covers changed as a title “moved up or down the paperback hierarchy, [for example] from the relatively upscale NAL [New American Library] to the much less savory Berkley Books.” She’s also great on the lurid imagery’s coded messages, such as the slip strap falling off a shoulder that signaled post-World War II anxiety about unbridled female sexuality.

Transgressive women weren’t just pulp cover girls, Rabinowitz demonstrates. They were authors and readers, as were African-Americans, gays, and lesbians, all given voice and acknowledged as consumers by the paperback industry. Distributed to newsstands and drugstores, pulp books were accessible to a broad spectrum of society, including members of America’s newly prosperous working class. Paperback publishers were willing to sign up anyone whose writings would sell, and they were also willing to help sales along with suggestive art and tantalizing cover lines like the one that proclaimed George Orwell’s anticolonial novel, Burmese Days, “A Saga of Jungle Hate and Lust.”

For a vivid decade or so, sleaze was, somewhat paradoxically, a force for literacy and empowerment.

|

Pulp paperbacks routinely blurred the boundaries between high art and low entertainment, serious nonfiction and salacious stimulation. One of the first books published in America about the Holocaust, a memoir titled Five Chimneys in hardcover, in 1947 was sensationally retitled I Survived Hitler’s Ovens for paperback, sporting the cover blurb, “The Uncensored Truth.” Cold War fears could be manipulated through misleading art to attract readers to daunting material. Fronted by an illustration depicting a white couple walking down a deserted road, the 1954 Bantam edition of Hiroshima packaged John Hersey’s sobering account of the devastation wreaked by a U.S. atom bomb as, in Rabinowitz’s sardonic assessment, “a garish nightmare of American annihilation—presumably, given the title, by the Japanese.

Pulps also blurred stylistic distinctions. Richard Wright’s 12 Million Black Voices appropriated the tabloid newspaper format to relate the history of African-Americans. Jorge Luis Borges’s first story in English translation appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, sold on the same mass-market racks as novels like Ann Petry’s The Country Place and Vera Caspary’s Laura, which slipped modernist techniques—interior monologues, multiple narrators with conflicting points of view, stories told through (fictional) documents—into murder mysteries and tales of small-town scandals.

4 comments:

Good point, she makes. And now the savior may be Jeff Bezos and his Kindles, or is "savior" and "Bezos" oxymoronic? The name sure as hell has a darkling ring to it, don't it.

I love that cover, too. And I felt the same as you did about the article. Not bad information, but the tone put me off.

Liked Smith's review above which makes similar observations to what Curt Evans had to say about Rabinowitz' "lapses into inpenetrable academese." Love that phrase!

Had to go find the New Yorker article by Louis Menand. I didn't see anything wrong with his straightforward reporting of Rabinowitz' book until I got to his supercilious references to sleazy and sordid pulp fiction titles. It's always the same with these types, isn't it? Interesting that book cover designs are STILL one of the main deciding factors in whether or not someone will buy a book.

Read Menard's essay and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Post a Comment