from http://www.maxallancollins.com/blog/

Like most writers who’ve had any sort of success – and this seems to apply particularly to mystery writers – I get questioned frequently about influences. If you’ve followed these updates or seen me on a convention panel or maybe just chatted with me, you know the list: Hammett, Cain, Chandler, Spillane, and a bunch of others. Writers all.

And I sometimes mention – as do such contemporaries of mine as Bob Randisi, Ed Gorman and Loren Estleman – the impact that series television had on me as a writer. Not every writer is secure enough to admit being influenced by what we used to call the boob tube (I always hear Edith Prickley saying that). But those of us who grew up in that wave of TV private eyes in late fifties were probably as influenced by such shows as Peter Gunn, 77 Sunset Strip, Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer, Perry Mason and Johnny Staccato (among others) as we were Hammett, Chandler and Spillane.

More often (though still relatively seldom) you’ll hear a mystery writer admit to having been influenced by filmmakers. I frequently mention directors Alfred Hitchcock and Joseph H. Lewis, and such movies as Kiss Me Deadly andChinatown. Add Vertigo to those last two and I would challenge you to find many novels that stack up, even by the masters.

But it’s rare that any writers think to mention the influence actors have had on their fiction. I know that Italian western-era Lee Van Cleef influenced my Nolan series, for example, and Bogart is someone that writers sometimes aren’t embarrassed to cite as influential on their work. Not often, but it happens.

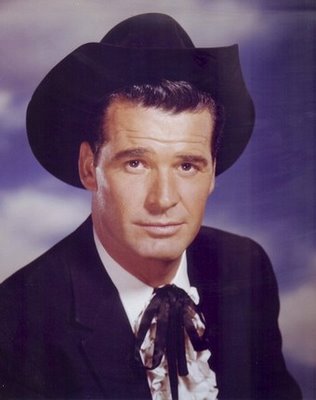

For me, the passing of James Garner – a man I never met and never had contact with – reminded me how big an influence this actor was on my life and my work. Before the TV private eye fad, there was the western craze, and discovering Maverick at a very young age shaped me in a way that rivals any parent or mentor. Now of course Roy Huggins had a lot to do with that, as the creator and frequent writer on the series, but it was Garner who brought life to the character, whose like we’d never seen.

Bret Maverick was a big, good-looking guy, able to handle himself with his fists and passably well with a gun (despite his claims at being slow on the draw). But he would rather charm or con his way out of a jam than fight or shoot. He was quick with a quip but never seemed smug. He was often put upon, and didn’t always win. Though he was clearly better-looking and more physically fit than your average mortal, he conveyed a mild dismay at the vagaries of human existence. And he did all of this – despite (or in addition to) Roy Huggins – because he was James Garner.

Garner’s comic touch was present in much of his work, and of course Bret Maverick and Jim Rockford were essentially the same character. And no matter what literary influences they may cite, my generation of private-eye writers and the next one, too, were as influenced by The Rockford Files as by Hammett, Chandler or Spillane. The off-kilter private eye writing of Huggins and Stephen Cannell made a perfect fit for Garner’s exasperated everyman approach, but it was just notes on a page without the actor’s musicianship.

Not that Garner couldn’t play it straight – he was, in my opinion, the screen’s best Wyatt Earp in Hour of the Gun, and as early asThe Children’s Hour and as late as The Notebook he did a fine job minus his humorous touch. But it’s Maverick and Rockford – and the scrounger in The Great Escape, the less-than-brave hero of Americanization of Emily, and his underrated Marlowe – that we will think of when Garner’s name is mentioned or his face appears like a friendly ghost in our popular culture.

Garner’s attempts to resurrect Maverick were never very successful – Young Maverick a disaster, Bret Maverick merely passable, though his participation in the Mel Gibson Maverick film was on target. I was fortunate to get to write the movie tie-in novel of that and – despite an atypically mediocre William Goldman script – had great fun paying tribute to my favorite childhood TV show and to the actor I so admired. (If you read my novel and pictured Gibson as Bret Maverick, you weren’t paying attention.)

Like all of us, Garner was a flawed guy, though I would say mildly flawed. Provoked, his easygoing ways flared into a temper and he even punched people out (not frequently) in a way Bret Maverick wouldn’t. He never quite came to terms with how important Roy Huggins had been to the creation of his persona, and essentially fired him off Rockford after one season. The lack of Huggins and/or Cannell on Bret Maverick was probably why it somehow didn’t feel like real Maverick.

Garner had great loyalty to his friends, however, and as a Depression-era blue collar guy who kind of stumbled into acting, he never lost a sense of his luck or seemed to get too big a head. He resented being taken advantage of and took on the Hollywood bigwigs over money numerous times, with no appreciable negative impact on his career. He was that good, and that popular.

When he gave a rare interview, Garner displayed intelligence but no particular wit, and it could be disconcerting to see that famed wry delivery wrapped around bland words. Yet no one could convey humor – from a script – with more wry ease than Jim Garner. Perhaps he was funny at home and on the golf course and so on. Or maybe he was just a great musician who couldn’t write a note of music to save his life.

It doesn’t matter. Not to me. He influenced my work – particularly Nate Heller – as much as any writer or any film director. He was a strong, handsome hero with a twist of humor and a mildly exasperated take on life’s absurdities. I can’t imagine navigating my way through those absurdities, either in life or on the page, without having encountered Bret Maverick at an impressionable age.

Watch something of his this week, would you? I recommend the Maverick episode “Shady Deal at Sunny Acres,” which happens to be the best single episode of series television of all time.

J. Kingston Pierce has a wonderful post on Garner at the Rap Sheet, with links to his definitive (and rare) two-part interview with Bret Maverick himself.

M.A.C.

No comments:

Post a Comment