He Had It Comin’: Western-Style Revenge

JAKE HINKSON from Criminal Element

Not only men take revenge

The starkness of the American west has always lent itself to tales of violence and retribution. This is the essence of the Western: men and women, squinting to the sun, square off against one another over primal issues. Love. Hate. Greed. And, of course, revenge.

Dramatically speaking, vengeance can be a one-note affair. As an idea, “I hate you, and I want to kill you” is fairly straightforward. And yet revenge stories often become complicated affairs (just ask Hamlet). Revenge may seem simple, may seem like it will solve everything, but it never really does. In the Bible, God warns against revenge, saying, “Vengeance is mine.” Why does the good lord hog all the retribution for himself? Because, as it turns out, human beings tend to make a mess of revenge.

As a genre, the Western is uniquely suited to the subject of revenge. After all, the settling of the west was a bloody affair involving the decimation of societies, feuds between individuals, and disputes over land and material resources. There was a lot of revenge to go around.

You can see this in some of the genre’s premier works. Here’s a primer on revenge, western style:

Ringo Kid, the role that made John Wayne

STAGECOACH (1939)—Director John Ford’s epic tale of a group of strangers traveling through hostile territory made a superstar out of a B-actor from Iowa named John Wayne. As the Ringo Kid, Wayne is hunting down the gang of brothers who killed his family. In keeping with the upbeat nature of the film, Wayne’s path to revenge is relatively uncomplicated, and his shoot-out with the brothers ends on a note of triumph. The path of revenge wouldn’t always be so easy for Duke, though.

RED RIVER (1948)—Howard Hawks centered his Western masterpiece around the conflicts that emerge between middle-aged rancher John Wayne and his adoptive son Montgomery Clift on a long cattle drive from Texas to Missouri. Unable to pick a winner in this battle of wills, Hawks and his collaborators trip at the finish line and deliver a silly ending. Up until the last two minutes, though, this is probably John Wayne’s best movie. Obsessed with killing the son who has (in his mind) betrayed him, Wayne plays to the dark side of his own persona. He was never scarier, and yet he never seemed more like John Wayne.

Searching for vengeance...

THE SEARCHERS (1956)—Not to be outdone, John Ford took Wayne to even darker places as a racist ex-Confederate soldier searching for his niece among the wives of an Indian chief named Scar. A flawed film in some ways, it deserves credit for letting Wayne’s hate burn hot and bright out there in the desert sun. The scene of Wayne scalping his enemy is, while not graphic, still shocking. The film’s closing shot of a “triumphant” Wayne walking dejectedly off into the empty desert is a haunting image of the futility of revenge.

WINCHESTER ’73 (1950)—Anthony Mann, perhaps the master of Western violence, directed Jimmy Stewart in the stark tale of a man searching for the killer of his father. The film was to be the first in a series of five hard-hitting collaborations between the director and star. Like many of their films, Winchester ’73 is deceptively simple, but it grows in power the more you see it. Viewers familiar only with Stewart’s nice guy roles will be stunned to see how nasty the guy could be in a fight. See also: Bend of the River, The Naked Spur, The Man From Laramie, and The Far Country.

Not only men take revenge.

THE FURIES (1950)—The same year he first teamed with Stewart, Mann also made this fascinating revenge tale starring Barbara Stanwyck as the daughter of land baron Walter Huston. When her father hangs her lover, Stanwyck swears to take away everything from the old man. And Barbra Stanwyck don’t make no idle threats. The father-daughter standoff is unique in Westerns, but the spare imagery and savage emotions make this a nice companion piece to Winchester ’73.

THE GUNFIGHTER (1950)—Gregory Peck stars as a weary gunslinger being hunted by three vengeful brothers in this meditative “inside Western” from director Henry King. Rather than the outdoor epics of Ford, Hawks, and Mann, King essentially directs this as a chamber drama, with our hero quietly awaiting the death he knows is coming. An odd film in many ways, it gives a different spin to the usual revenge narrative.

THE BRAVADOS (1958)—Peck and King teamed again for an even darker, more complicated look at vengeance with this tale of a widower hunting down the men who murdered his wife. He extracts his revenge, but he doesn’t get what he expects from it. Based on the novel by pulp writer Frank O’Rourke, this underrated gem is the rare Western that openly questions the ethics of revenge.

Vengeance under a high noon sun...

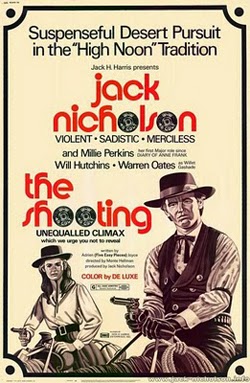

THE SHOOTING (1966)—Director Monte Hellman directed this bare-bones production with a simple aesthetic in mind: all you need is a camera and some actors, a landscape and a story. Filmed in the rocky deserts of Utah with a crew of seven people, it tells the story of two men (one of whom is ex-gunslinger Warren Oates) hired to ride along with a strange young woman (Millie Perkins) through uncertain country. Then the boys notice they’re being followed by a stranger in black (Jack Nicholson). One of Hellman’s best films, and a revelation if you’re only familiar with late-career self-parody Nicholson. This guy used to be insanely good in movies.

RIDE IN THE WHIRLWIND (1966)—Shot at the same time as The Shooting, in the same Utah location, with some of the same actors, this is another stripped down revenge tale from Monte Hellman. The films stars Nicholson as one of three men unjustly being hunted by an angry lynch mob and co-stars Harry Dean Stanton as a bandit named Blind Dick. I’ll stop writing about the movie now, since I assume you’ve already hopped over to Netflix to order it.

Clint Eastwood, king of the revenge western

UNFORGIVEN (1992)—It’s hard to narrow down the Eastwood revenge-flick of choice since Clint spent most of his career vengefully blowing people away, including twice coming back from the dead to avenge his own murder (High Plains Drifter, Pale Rider). Having said that, Eastwood seemed to sum up everything that really needed to be said about revenge in his 1992 masterpiece, Unforgiven. Dark and violent, the film is also strangely haunting, a perfect marriage of acting, writing and directing. Unforgiven’s most iconic exchange seems to encapsulate the Western’s final take on revenge: when a callow gunslinger named the Schofield kid says of two murdered cowboys, “Well, I guess they had it comin’,” Eastwood simply responds, “We all got it comin’, kid.”

1 comment:

This is a fine collection of mythic revenge stories set in a mythic West. And yet it misses the single most important revenge story of them all, High Noon.

Post a Comment