from the New York Times

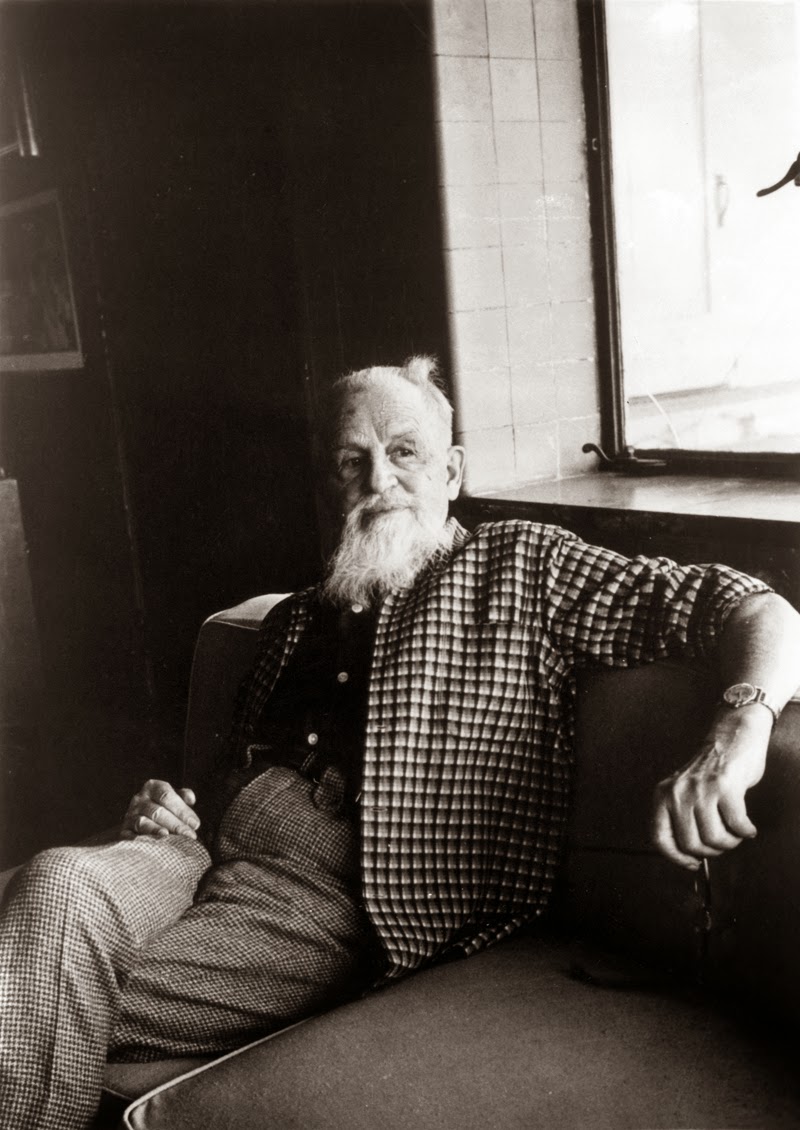

Jeremiah Healy, Who Created Boston Private Eye,

Dies at 66

Share This Page

Jeremiah Healy, an acclaimed mystery writer whose

best-known creation, the conflicted private investigator John Francis Cuddy,

was a Vietnam veteran who solved crimes and confronted sensitive political

issues with compassion, wit and the occasional burst of violence, died on Aug.

14 in Pompano Beach, Fla. He was 66.

His fiancée, Sandra Balzo, said Mr. Healy

committed suicide and had suffered from depression for many years.

Mr. Healy, a Harvard Law School graduate who

began writing his books while teaching law, introduced Cuddy with the

publication of his first novel, “Blunt Darts,” in 1984. He went on to write a

dozen more and two short-story collections about the jaded but earnest sleuth

who typically plied the waterfront and back streets of Boston. Many of the

books were finalists for the Shamus Award, given by the Private Eye Writers of

America, and one, “The Staked Goat” (1986), won it.

John Cuddy was a former military police officer

and widower who read deep into newspapers and took long, thoughtful jogs across

his historic city. He killed when he needed to kill, but readers were as likely

to remember his vivid observations of the people and places he knew as they

were the violence.

“The morgue was built back in the ’30s,” Mr.

Healy, in Cuddy’s voice, wrote in “Rescue” (1995). “It was almost new in

November 1942, when the bodies from the Coconut Grove fire were taken there by

the hundreds, at least as many people standing in line outside the mortuary

that next Sunday morning, waiting to identify friends and loved ones. Now,

though, the morgue was literally falling down on the pathologists and

technicians who work inside it, gaps in the hung ceiling where the rectangles

of Styrofoam have crumbled onto the examining tables and slabs.

“They’ve been talking for years about moving the

place out to Framingham on state-owned land that would be a cheaper site than

building or renovating in Boston. Until then, the medical examiner struggles

with an inadequate budget and a pared-down staff and conditions more

appropriate to the end of the 19th century than the predawn hours of the 21st.”

Mr. Healy explored topical issues, including

assisted suicide in “Right to Die” and urban-rural divisions in “Foursome.” He

wrote about date rape, racism, AIDS and homelessness.

Reviewing “Shallow Graves” in The New York Times

in 1992, Marilyn Stasio called the Cuddy books a “superior series” and cited

Mr. Healy’s “mousetrap timing and tight plotting.”

“Using fine brush strokes when he likes his

subject and sharp pointillist jabs when he doesn’t,” Ms. Stasio wrote, “the

author executes one of his better studies on Primo T. Zuppone, a mob enforcer

whose aesthetic sensibility belies his skill at smashing kneecaps. ‘Cuddy,’ he

advises the detective, ‘you got to look for the art in life.’ If Cuddy doesn’t

quite get the message, we do.”

Jeremiah Francis Healy III was born on May 15,

1948, in Teaneck, N.J. He graduated from Rutgers University in 1970 and from

Harvard Law School in 1973. He worked in private practice for several years

before joining the faculty of the New England School of Law in Boston, where he

taught from 1978 to 1996.

Mr. Healy wrote a few novels that were not part

of the Cuddy series, and he wrote a separate three-book series, under the

pseudonym Terry Devane, that featured a young lawyer, Mairead O’Clare, whose

toughness was evident in high school, where she made the boys’ hockey team.

In addition to Ms. Balzo, Mr. Healy’s survivors

include a sister, Pat Pinches. His marriage to Bonnie M. Tisler ended in

divorce.

Mr. Healy, who lived in Pompano Beach, was a past

president of the Private Eye Writers of America and the International

Association of Crime Writers.

Like some mystery writers and so-called midlist

authors, he began struggling to find publishers when the industry began

contracting in the late 1990s. The last Cuddy book, “Spiral,” was published in

1999 and took place mostly in Florida.

Ms. Balzo, who also writes mysteries, said Mr.

Healy had drafted two screenplays in recent years and was planning to revive Cuddy

in a new book. Research material for it occupies seven feet of shelf space in

his office, she said.